A History of the Clint Eastwood Classic Thriller ‘The Beguiled’ (1971)

Filmmaker Jay Woelfel writes about the fascinating story behind the original film.

The Beguiled is a 1971 drama about an injured Union soldier who cons his way into each of the lonely women’s hearts, while imprisoned in a Confederate girls’ boarding school, causing them to turn on each other, and eventually, on him.

Clint Eastwood acknowledges THE BEGUILED as an important step towards him becoming, as he puts it, something other than just a guy with a gun. By today, Eastwood has pretty much done it all but he started as a Universal Studio contract player in the 1950’s who was told at one point his Adam’s apple was too big for him to be a star. He did get to kill a GIANT TARANTULA, however his movie career went nowhere.

He finally got somewhere by appearing in the successful Black and White Western TV series RAWHIDE, known most frequently nowadays from the song. He was the co-star of the show—still not top billed. So Eastwood took a chance at having a movie career by going to Italy to make a low budget Western that was a rip off of a Japanese rip off of a still unfilmed novel called RED HARVEST. European producers all wanted a name that meant something in the United States. It was, they felt, the only way to get their little European films released in theatres in the United States. The best they could do in this case was a TV name of sorts in Eastwood. Eastwood figured he’d see Italy, and Italian women, and nobody would probably ever see or know about the movie if it failed. He figured he had nothing to lose.

Though the rest is history, at the time Hollywood and critics still didn’t know what to do with him. The only reason we know Spaghetti Westerns as a genre (and Germany made westerns for years that still almost nobody knows about) is because of what became known as THE MAN WITH NO NAME series of films starring Eastwood and directed by Sergio Leone, but the term was a derisive one at the time. Let me correct myself, critics did know what to do with Eastwood and that was to deride him and these strange out-of-sync violent Westerns made cheaply in the remaining shadows of Mussolini’s Fascism or under the carefully turned away eyes of still existing WW II dictator Franco’s Spain.

Audiences though endorsed the films and he was a budding international movie star. He became known as Squint Eastwood and he would age well, critics said, because he didn’t or couldn’t act, rarely spoke, and never changed his expression on screen. Nevertheless Eastwood starred in other European filmed movies, like the enjoyably incoherent WHERE EAGLES DARE with real actor Richard Burton alongside to do most of the talking. Eastwood does however fill both hands with machine guns, which he fires in unison—inspiring Jackie Chan and others to double fire guns in films to this day.

If you find early review books of films on TV and video you’ll see it took a long time for the critics to come around to what the public embraced in these Eastwood Euro-Oaters. (Western fans and film historians remain to this day a bit divided on including these films into the canon of Westerns as they weren’t made in or by Americans, I suppose.)

John Wayne, who according to director Don Siegel, found Eastwood’s films to be violent and profane, kept the otherwise dying theatrical western genre alive, even leading Eastwood to the musical western PAINT YOUR WAGON, but it only proved the limits of his star status even within in the genre. Various other Hollywood attempts to make Spaghetti style westerns would awkwardly follow.

During this transitional phase of Eastwood returning home to make films, he was directed by Siegel—a man whose career predated Eastwood’s and who bounced around uncertainly between lower budget theatrical films—including what Siegel himself felt was his most significant film, INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS—and television. Star and director made the successful but not really very good modern western COOGAN’S BLUFF, which inspired the long running and better TV series McCloud and the underrated Spaghetti type western comedy TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARAH. The two men liked and understood each other.

Eastwood was feeling disappointed in the films he was making, the anachronistic Hippie WW 2 film KELLY’S HEROES and was presented by Universal producer Jennings Lang with a novel that Lang liked but didn’t know what to do with. That novel, THE BEGUILED, so riveted Eastwood that he read it in one sitting and couldn’t decide if he loved it or hated it. He gave the book to Siegel, hoping Siegel would tell him it was terrible. Siegel read it and loved it. He sang the Civil War tune, THE DOVE, a song that Eastwood’s hesitant voice quavers out at the start and end of the film to get Eastwood out of his trailer and into the movie.

Siegel in his sometimes factually dubious autobiography A SIEGEL FILM, recalls in detail only and specifically the opening of the film. Title sequences weren’t unusual then but remember that Siegel in his early days had first worked on titles and montage sequences for Warner Brother’s films before he got to direct features of his own. THE BEGUILED features several terrific montage sequences showing Siegel’s skills at applying them to film storytelling, most notably a dark sexual fantasy sequence over overlapping images.

I’ve shown the opening to this in film classes to demonstrate how to use sound and music to both start up and set up a film. It begins with a title sequence of real civil war photos of preparing for a battle, the battle, and the dead afterwards. These are mostly real photos. One of the photos that Siegel claims is genuine shows a wounded soldier who looks exactly like Eastwood, too exactly if you ask me to not be him, but regardless over this sepia tinted photos we hear a faint drum roll and the sounds of battle and that song Siegel sang to lure Eastwood that end with the words “And death will come marching to the beat of a drum.”

The image turns slowly to color as a young girl picks mushrooms beneath the Spanish moss that hangs from the trees and beautiful real music, from Lalo Schifrin, plays. The little girl is Pamelyn Ferdin at the time an instantly recognizable child actor who also first voiced Lucy in the Peanut’s movie. Amid the mushrooms she comes across a bloody boot worn by a Union Soldier named John McBurney (Eastwood) who falls forward and collapses on the ground surrounded by mushrooms spilled from her basket.

These few images put together essentially tells us the entire story the film will tell. They exchange a few words and a Rebel patrol is approaching. In the novel it’s clear he doesn’t want her to yell out to the troops and turn him over as a Yankee soldier. In the film it’s more sudden as he says she is ‘old enough for kisses’ and then plants a very adult kiss on her lips as we dreamily superimpose the enemy troops riding towards them. In the remake, which I won’t mention often in this article, much of the dialogue from the novel is used in this first encounter, here it’s as wordless as possible. But neither film uses the rest of this key line of dialogue from the book. “Old enough for kisses then, and old enough to hate.” That’s the key to the central situation and conflict in story.

RELATED: Read our review of the Sophia Coppola remake of The Beguiled

The little girl takes this rogue desperate male back to the isolated and equally desperate girls school that represents the south in the last stages of a war they will lose. She’s young and you might wonder if she knows good mushrooms from the poisonous ones, and that’s the question the film and story will devote itself to this man she’s brought back from the forbidden woods. Is Eastwood’s character, McB our hero or the villain of the piece, and just how innocent are all these “girls.”

The novel uses different character’s points of view to tell the story, a device few if any films actually try to employ—other than the famous CITIZEN KANE and even more effectively in RASHOMAN. If I can digress a bit, the novel THE TAKING OF PELHAM ONE TWO THREE also uses this device. The recent remake of THE BEGUILED claims to follow the novel but retains credit for this film’s screenwriters and doesn’t attempt to use the varied point of views. This original film does retain some of this approach in the form of internal character voice overs or in Mcb’s case flashbacks showing exactly how much he is lying. There is also, typical of Siegel, occasional rather shaky handheld camera when you might least expect it sometimes used as point of view shots especially early on and towards the end to show the helpless McB surrounded by the women and his environment.

The film is the first photographed by Bruce Surtees and it seamlessly matches location work with studio interiors. Complicated actor and camera blocking exist throughout the film but you are never aware it’s being staged or framed—the style is expressive and unpredictable.

What we have here potentially is really an erotic thriller, or if you take the thrills out a Southern Gothic Romance—two commercial genres with deservedly bad reputations. You have the stud outsider amid what we can quickly guess will be lonesome girls and in lesser hands lots of sex ensues until you have enough running time to call it a movie. The film was made when American films were beginning to show nudity and crudity, pushing the limits of what could be shown and dealt with. These limits would soon reach their end with true hard core pornography that seemed poised for a moment to perhaps become a part of mainstream pop culture.

In fact the first screenwriter on the film had written his draft as a romance and with a happy ending. Don Siegel rejected the script and always saw the film as a horror film along the lines of Ambrose Bierce. Bierce was a famous pop culture writer—of the time—a newspaper figure who became known as Bitter Bierce, writing in newspaper-like style and structure criticized by literary critics as too coarse to work as fiction. Again the critics didn’t stop Bierce’s career and he even managed to literally vanish into history riding off into the Mexican Revolution in search of a pre Hemmingway-ish finale purely macho and male spirit quest for a good death. Gregory Peck in his final film portrays Bierce’s last days in the film THE OLD GRINGO.

Bierce’s public fame grew from his own origins as a soldier in the Civil War and in his uneven but at most times powerful fictional short stories about that war. Bierce’s horrors of war are frequently supernaturally charged and a preposterous mixture of bizarre events revealing little difference or distance between the living and the dead or the moral and immoral. His writings about the civil war are considered to be the best fictional expression of that war. Bierce remains almost untouched by filmmakers and this film does have those qualities.

Another possible inspiration of the story is the post war sequence in GONE WITH THE WIND where a Yankee confronts Scarlet in her ruined mansion with unsavory intentions and is killed. It’s like that one section is worked out in greater detail here—including a mustache wearing brother character. GONE WITH THE WIND casts a long shadow and created a number of Southern drawl clichés—all of which THE BEGUILED under Siegel’s direction avoids. The southern accents are lightly laid into the film, never distracting or forced. The dialogue is free of too many “authentic” historic phrases.

Now it’s worth noting that THE BEGUILED came during an almost equally divisive war for the United States, the Vietnam War, though the book was written in 1966 before public opinion became overwhelmingly against it. THE BEGUILED is an anti-war movie as some argue any truthful story of war must be anti-war in the end. To reference another filmmaker, and war veteran, Sam Fuller’s ultimate thought on war was that the only glory in it was surviving. In THE BEGUILED there is certainly no glory in surviving but that’s what all the characters are trying to do and they don’t care about anyone surviving other than themselves as it turns out.

Though there are virtually no war or battle scenes and much of the real life Civil War details in the novel are left out of the film—probably just as well. The threat of his being captured is kept alive and suspenseful throughout the film. Visually we see the plantation house/school as a trap for all of them. The staircase railings being like prison bars and even some over the shoulder shots where most of the person is blocked by the back of the other character. Light often falls on only parts of faces and in one scene with threatening Southern soldiers a moving lantern constantly shifts shadows and distorted light across the scene.

Eastwood explains his character on a Blu-Ray release, as wanting to stay out of the war so badly that he’s willing to exploit his situation as the only man in town and to try to do what his MAN WITH NO NAME did famously, which is play both sides against the middle. Unfortunately he turns out to be the middle. Eastwood says his approach to the part was that the character takes things too far and that gets him into trouble. The film was being made and released in the midst of the sexual revolution a Battle of the Sexes, which gave rise to the women’s liberation movement on one side and the Playboy and rise of more graphic Penthouse Magazine’s culture of women as sexual objects.

Extremes, like these, have continued to be the case in the world since then, the middle of the road position, the binding balance, could be lost between the two oppositely polarized extremes. Here we have the man from the North and the women from the South—does it get any more obvious than that?

THE BEGUILED is a war between the sexes in microcosm. Though criticized as sexist then and now, both sexes in the story are aware, though maybe not at the same time, of what they are doing. Neither side is represented as being driven by the situation to become more vile or more virtuous than the other. The film can be embraced by man or women haters in that regard.

Siegel points out that Eastwood doesn’t care about his image and this film puts his image to the test. That image was as one of the 1960’s brand of anti-hero stars, which Sean Connery as James Bond and Steve McQueen also brought to popularity. A key challenge is for us to actually fear that Eastwood could seriously be in danger from a bunch of Southern Bells after all the surly brutes and Nazi’s he’s killed off in his career up to, and since then.

Eastwood rarely dies in his films, though he says it’s all about if the story requires you to die—in this case—SPOILER ALERT, well, he does. And though we side with his character because he’s Eastwood and because he’s outnumbered, he certainly is willing and able to act in this film, maybe even overact a bit—though that doesn’t seem the case now as it did when the film came out and his silent low key style was all we thought he had to offer. He’s subtle and ever changing in this film, he is never the stoic man audiences would normally expect. It’s one of his best performances amid a film full of good performances.

When the film came out critic Vincent Canby in the New York Times said of the film: “People who consider themselves discriminating moviegoers, but who are uncommitted to Mr. Siegel will be hard put to accept it, other than as a sensational, misogynistic nightmare.”

Canby’s review is snobbish as he explains that the plot has too many twists in it and that while he appreciates it in terms of how it is different and unusual coming from director Don Siegel but that this will be lost on the general public. At any rate both star and director wanted to make it because of the reason’s Canby both dismissed and gave it credit for.

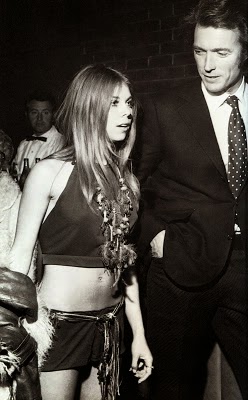

The film presents the women at first as being maternal—they have the injured man they must heal. There is a parallel of a wounded bird the little girl Amy is also caring for. The head of the school is played by Geraldine Page who was no stranger to repressed desires and aspirations as she was nominated for an Oscar for SUMMER AND SMOKE, and if you believe gossip she suffered somewhat at the hands of her own husband in real life, actor Rip Torn. Another performer with career and real life parallels in Elizabeth Hartman who became known for playing the blind and in other ways abused girl in A PATCH OF BLUE and who lead a troubled real life, leading to her own suicide. Also trapped and teasing is Jo Ann Harris, who soon became Eastwood’s girlfriend on set and for a time afterwards.

The most lurid element of the movie is the incestual relationship in the head mistress’ past with her now vanished brother, this laid out clearly in a series of short wordless flashbacks. By the end, theses flashbacks reveal he may have been killed trying to rape Hally, the school’s remaining slave.

The pull and tug of each woman against the man are different from each other and Mcb reacts as he feels is appropriate. For example, he resists the girl who most wantonly is after him. As I just mentioned, the school retains a slave, well played by Mae Mercer and McB assumes she will side with him because his side is there to free the slaves. She points out he’s a slave too because he’s a soldier.

The music too attaches to the characters. The slave, Hally, makes her own music by constantly humming—this seeming like an idea from post production and sometimes not too convincingly crammed in between on location dialogue. There is a medieval theme–to go along with an idea McB suggests that the girls are like princesses waiting to be rescued by their prince, the military drums, and a harpsichord theme, and a frightening organ driven religious one—all elements you wouldn’t think of coming from Lalo Schifrin the master of Cuban rhythms in the then modern guise that made him so successful but also put him out of fashion. His score for this film is sadly unavailable in any format.

If you want to get all Freudian, the Union soldiers leg wound can been seen a phallic and the women are tending to it to heal it. Siegel even reportedly said the whole film is about them trying to castrate him. So as things heat up and he becomes mobile of course he no longer needs the women to be maternal and exploits them sexually to try to escape the war or perhaps, if you go with the time the film was made in, live in some sort of male Harem fantasy.

This all leads to a night in which three women expect him in their beds at the same time and so his harem desires are discovered, well, Hell hath no fury … This is the key castration of the film as his supposedly now, according to the scorned head mistress, incurably broken leg is cut off. Is it really an act or revenge on the part of headmistress or does Mcburney just assume it is as he can’t accept being what he says rather clunkily at one point in the remake as being, “not even a man” without his leg.

The amputation scene is truly horrifying, using no music and much but almost invisible editing—the entire film is brilliantly edited in this almost invisible way. As they start to cut every shot is squirm inducing, especially a shot of the about be dead foot wriggling its toes. Each character is kept in the action which takes place, as many key scenes do on the dinner table—as if he’s the meal being carved up this time.

You can see this amputation either way, I don’t see it as being clearly revenge and in the moral universe of the film he deserves it. Once he wakes and finds his leg gone (another harrowing scene) his hostility explodes and in a bid for control, he explains he will now be with any of the girls who “who desire his company.” Mcburney choses one woman as his—again does he really love her or does he just use her as he must now have help to escape. But the audience is on his side by this point as the Page, the Head Mistress, seems to firmly and totally be his enemy as this is, after all, her school and her girls.

Amy, the young girl who brought him to the school in the first place has a heartbreaking scene with McB in which she confesses her love, and in his rage he accidentally kills her, unfortunately too green and rubbery looking, pet turtle. Eastwood expresses such shock at his own act of violence here and we see him as genuine.

But it’s too late, the turtle is the final straw, we’ve come full circle. The headmistress sends out the young girl now certainly “young enough to hate.” to pick mushrooms that will kill him, either because she can be justifiably the best executioner.

After the Mcb’s murder by mushrooms, the headmistress shows her return to control by teaching the girls how to properly sew up the sack they put him in and the film ends as they drag him away as the mournful civil war song is sung by the dead man and the color drains from the image of Spanish moss draped trees and the sounds of morning doves taking over from Eastwood’s voice.

What makes a good film great is that it can be open to interpretations that are equally valid, of course too many wanna’ be filmmakers try to be all open ended in pretentious ways that are hard to stomach and really are just cop outs for juvenile filmmakers. After all, who are the beguiled? The women or the man? My answer is … both.

Despite the possibly trendy and topical elements the film juggles all too well, it failed to reach an audience. “It was not particularly successful” is how Eastwood describes it, and I assume he means just commercially. This being the sole way the film business traditionally judges or expresses satisfaction or lack of with a film. Siegel said in perhaps typical fashion for any director that Universal botched the release. Again this is a cop-out used often by creators of films that fail to make money. But Siegel was not some first timer and makes good points that the film was released like any other Eastwood movie not as an arthouse movie. He said it should have been released at Cannes and the French would have loved it. Let me point out that this was exactly how the remake was handled and it won director Coppola a best directing award.

Instead he said they released it with posters that made it look like Eastwood won the Civil War single-handedly. This is not entirely true though some of the release posters do try for this, and Eastwood is there, still “the guy with a gun” that Eastwood eventually managed to not be in his career. Siegel says he hired Edvard Gorey, to do some poster concepts for the film. If you don’t know his work, imagine some of Tim Burton’s style. It’d be fascinating to see Gorey’s unused concepts.

Regardless though, despite the French loving it, the film was released in the midst of the popcorn summer and sank without a trace. The remake sought to have a big name star, as the original had with Eastwood, but had to settle for Colin Farrell who though not bad in the film is a fading star who may soon be labeled a Movie Killer as he’s had more than his share of high profile bombs. Regardless, neither approach to this story found widespread commercial success.

I’ll say the title, though appropriate in many ways, is a poor one. It’s not a word many people use and it’s not used in the way people who do know it would understand. Other titles were considered JOHNNY McB (which is the nickname the main character prefers to be called by), NEST OF SPARROWS was another. Would a better title matter? And what would that be? That song has a line in it THE RAVEN WILL COME.

Despite this perhaps predictable commercial failure—the 70s did become a decade where commercially successful movies frequently had main characters dropping dead suddenly at the end of the film—but this was 1971 and being ahead of your time means you don’t make money even though you may make a minor or major classic as THE BEGUILED qualifies as. This is one of those films that got made almost by accident and with time that accident has become a very happy one.

Eastwood would next take on a directing career of his own and with some of the same sexual tension and danger subject matter in PLAY MISTY FOR ME, another film with a male who gets a little too arrogant at the wrong time and steps into a female trap. This time with only one woman, a stalker, and the film made lots of money.

Eastwood then did re-teamed with Siegel for a truly huge genre changing hit film, with Warner Brother’s, the studio that became and remains his primary home. The movie, DIRTY HARRY changed lots of things. For one, it successfully transitioned Eastwood into contemporary, rather than period, films, though he was still a guy with a gun. I’d love to go on and on about that great film, but this is not the time or place as THE BEGUILED deserves time and appreciation unto itself among Eastwood’s, and Siegel’s, best films. It has aged well, other than Eastwood’s perhaps anachronistic haircut and one misguided music cue with electric bass guitar in it.

And as Eastwood’s career has grown he has continued to work with people (while they were alive) he met working with Siegel—whom he had a bit of a falling out with as he did with his other directing mentor Sergio Leone. This I think hurt their careers more than Eastwood’s, and can probably be seen and easily forgiven as part of his directing career needing to become its own entity—the child turning into an adult and the frictions thereof. He returned to work under/with Siegel one last time for the creepy and effective ESCAPE FROM ALCATRAZ.

Though for a time after that Eastwood seemed to have become stuck in a rut of mediocre and some truly poor films he returned and has remained a significant director since the Western UNFORGIVEN and retired his revolvers, he says for good.

Since then it’s variety, that first was tried and only commercially failed with THE BEGUILED but has made Eastwood an institution that is still very active. While directing Kevin Costner in A PERFECT WORLD Costner threw a fit and went to his trailer. Eastwood shot the scene with Costner’s double and when Costner returned to shoot Eastwood reportedly told him. “I already shot it. We are here to make a movie not to F… around.” That could be his mantra and was definitely Siegel’s.

Jay Woelfle is an independent filmmaker. Learn about him here as he discusses his latest film.